Imagination, consolidation set the stage for today's facilities

In the late 1800s and early 20th century, a patchwork of municipal and regional utilities with imagination and muscle spread across northeastern Minnesota. Companies came and went in a parade of consolidations and business failures and acquisitions as they built much of the hydroelectric infrastructure still used today.

The roots of Minnesota Power go back more than a century to its immediate predecessor, the Duluth Edison Electric Co. Duluth Edison’s incorporation papers, read in part, “to improve, develop and use water power for heat, light and power purposes, and to develop, generate and use electric energy and currents for heat, light, and power purposes, otherwise than by water power.”

Until 1931, when the Hibbard Steam Electric Generating Station (now the Hibbard Renewable Energy Center) was built in Duluth, Minnesota Power’s electric generation was almost entirely linked to the streams and rivers in northeastern Minnesota.

The consolidation of several regional utilities into Duluth Edison in 1906 dovetailed with the completion of Thomson Dam in 1907, one of North America’s more ambitious hydroelectric projects. Thomson, proclaimed a writer for the Duluth Evening Herald newspaper, “was one of the great engineering feats of the 20th century.”

The scope of the Thomson project was impressive: the Thomson Reservoir is formed by a series of 25 earth and concrete dam structures totaling more than a mile in length and ranging in height from 4 to 50 feet. Construction crews built a canal two miles long to connect the reservoir with the forebay, a 40-acre holding pond almost 400 feet above the powerhouse. The Lower Gatehouse controls the discharge of water from the forebay into large steel pipes that convey water almost a mile to the generation turbines. The head—vertical drop between the forebay and the turbines—of 375 feet was recognized as having hydropower potential second only to Niagara Falls at that time.

But even before crews broke ground at Thomson, hydroelectricity was beginning to power businesses and towns elsewhere in northeastern Minnesota. At Little Falls, on the Mississippi River in Morrison County, the dam was formally dedicated on May 10, 1888. In 1890, the Little Falls Electric and Water Co. incorporated and entered into an agreement to provide electric lights for Little Falls streets.

Over on the Cuyuna Range, south and west of the Mesabi Range, the Cuyuna Range Power Co. built Sylvan Dam on the Crow Wing River and began generating electricity there in 1913. As demand for power on the Cuyuna Range increased, the company made plans for a second dam on the Crow Wing about 5½ miles upstream from Sylvan. The Pillager plant went into service in December 1917.

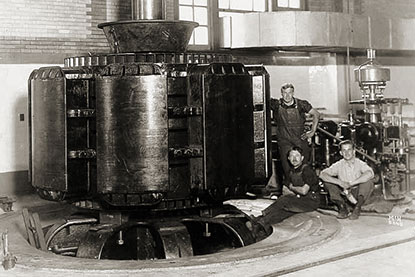

In 1914, workers installed Unit 4 at Thomson. Railroad tracks built into the generator floor allowed for installation and maintenance of the equipment.

In 1914, workers installed Unit 4 at Thomson. Railroad tracks built into the generator floor allowed for installation and maintenance of the equipment. Not quite a year later, in the fall of 1918, General Light and Power suffered a devastating blow to its transmission and distribution system when forest fires destroyed Moose Lake and Cloquet. The Weyerhaeusers had lumber businesses in Cloquet and decided to rebuild. Since they were literally starting from scratch, they included plans for a dam across the St. Louis River at Knife Falls. Construction began in 1920 and a second dam was built two years later at the site of the old Scanlon wagon bridge. Once the Scanlon dam was completed, both dams were placed under management of General Light and Power. About half their output was used to power the Weyerhaeuser lumber and paper mills.

In early 1923, consolidation of numerous regional utilities including General Light and Power, Cuyuna Range Power Co., Little Falls Water Power Co. and Minnesota Utilities Co. were consolidated and Minnesota Power & Light Co. was incorporated.

From 1923 to 1928, Minnesota Power & Light built Fond du Lac on the St. Louis River, Blanchard on the Mississippi River and Winton on the Kawishiwi River. It was one of the greatest periods of plant expansion in the company’s history.

Minnesota Power remained primarily a hydroelectric utility during the 1930s and up until World War II. By then, Minnesota Power had built a steam generating station that today is the Hibbard Renewable Energy Center. Even so, it was the hydroelectric facilities that delivered the bulk of the power to northeastern Minnesota during the war years. It wasn’t until after World War II ended that Minnesota Power made a pronounced shift from hydroelectric to steam power.

Still, the hydroelectric facilities continued to do their part in the decades following the war. And in 1982, Minnesota Power added to its hydroelectric fleet with the purchase of Prairie River Hydro from Itasca Paper Co. Today, the hydroelectric facilities reliably and efficiently produce power to help meet the energy needs of the 21st century.

Sources: "Northern Lights: An Illustrated History of Minnesota Power" by Bill Beck, Minnesota Power, 1986

"Electrifying a Century," by Bill Beck, Minnesota Power, 2006

From its earliest days, Minnesota Power has used water to generate electricity. Our hometown hydropower continues to play a vital role in our EnergyForward strategy to deliver carbon-free energy to our customers.

Our bold vision centers on our commitment to climate, customers and communities. We’re a clean-energy leader, already delivering more than 50% renewable energy and on our way to more than 70% renewable energy by 2030.

Learn more about EnergyForward here.

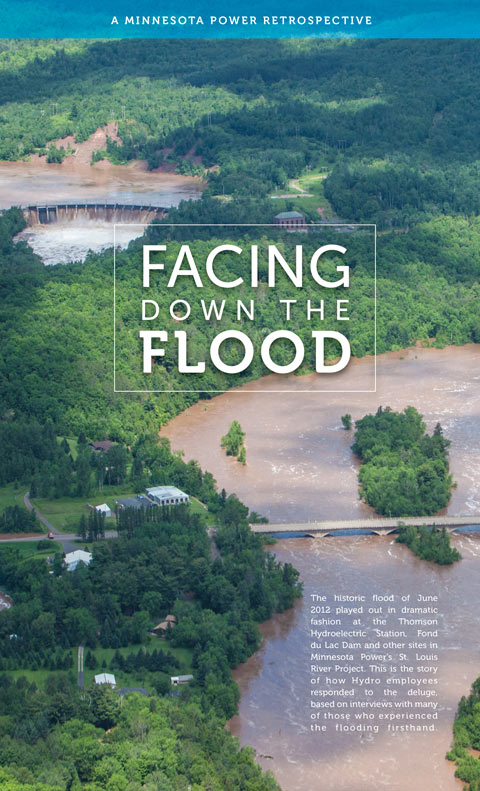

Employees, infrastructure face unprecedented challenges

In June 2012, a slow moving rainstorm across parts of northeastern Minnesota left homes flooded, roads washed out and lives changed.

The ground was already saturated from heavy rains in the prior month. Then, on June 19-20 as much as 10 inches of rain fell in some areas, causing flash floods and longer-term flooding. More than 1,500 homes and numerous roads and highways were damaged.

The St. Louis River grew from a pre-storm flow at the Fond du Lac Hydro Station of 5,000 cubic feet per second (cfs) to a record of approximately 55,000 cfs in the early hours of June 21. The previous record was 40,000 cfs on April 23, 1979. The U.S. Geological Survey also measured record flood stage levels and flows on the St. Louis River at Scanlon (downstream from Minnesota Power’s Scanlon dam). On June 21, the river level spiked from about 5 feet to a record peak of more than 16½ feet, surpassing the record of 15.80 feet in May 1950.

The flood played out in dramatic fashion at the Thomson Hydroelectric Station and other sites in Minnesota Power’s St. Louis River Project that Tuesday and Wednesday in 2012. Hydro employees worked through the night and day to respond to the unprecedented torrent of water moving through the system. Crews opened waste gates at reservoirs and dams, navigating their way through areas where roads suddenly became impassable. One employee was stranded alone at Fond du Lac dam overnight.

Wednesday morning, June 20, crews continued to clear debris through gates to keep the water moving down the river. By Wednesday afternoon, Knife Falls and Scanlon were offline. The basement at Fond du Lac, which was offline for repairs before the storm hit, was flooding. Thomson had shut down three of its six generators. By Wednesday evening, flooding at Thomson had grown worse and the last three generators were shut down. The control room maintained power and hydro operators continued to work from there.

One of the storm’s biggest blows to the hydro system came about 10:30 p.m. Wednesday when an earthen embankment at the forebay, a small reservoir that feeds water to the powerhouse, gave way. It took just minutes for the forebay to empty.

After the storm, crews worked for days to keep the gates clear of debris and the water moving. Other facilities quickly returned to normal but Thomson’s generators would stand idle until 2014.